D.L. Pearlman is a native of Norfolk, VA. He is the 2019 winner of the Edgar Allen Poe Prize from the Poetry Society of Virginia. His work has appeared in Cedar Creek Review, Hamilton Stone Review, Light, The Meadow, Poetry Quarterly and Poetry Virginia. Poet, professor, musician, and chronicler of decay, D.L Pearlman writes poetry that anchors readers in the natural world while leading them on a sensory tour of landscapes filled with both glory and decline. Pearlman’s collection Normal They Napalm the Cottonfields is the winner of the 2019 Dogfish Head Poetry Prize.

Broadkill Review: Congratulations on being named the winner of the Dogfish Head Poetry Prize 2019! What was your reaction when you were notified? Can you talk about your experience, some of the highpoints, and maybe something readers might not know about it?

D.L. Pearlman : I was just happy to be listed as a finalist, but when I was notified of winning, I told Linda I didn't believe it and asked was it real. When publisher Jamie Brown got involved, we ironed the manuscript like a shirt, going back and forth with layout structure, fonts, design and, embarrassingly, a few typos. I can't thank Linda, Jamie and Dogfish Head enough for their dedication and kindness.

BKR: Putting together a collection of poems is often a chore that can feel defeating to even the strongest of poets. What is your strategy when putting together a collection? What did you learn from putting together your first manuscript A Bird in the Hand is a Very Dumb Bird that helped you with the second? And what advice would you give poets putting together collections for contests like Dogfish Head?

DLP: My first book, A Bird in the Hand Is A Dumb Bird, features the subtitle "Selected Poems." It came from my first 20 years of writing and shows a lot of different range, structure and style. Normal They Napalm the Cottonfields is much more focused on the slow, subtle disappearance of Virginia and North Carolina's farmland and nature from the point of view of a traveling musician and photographer. As for manuscript construction, I used to try to build a logical framework, usually based on time/season. For Normal They Napalm the Cottonfields, I went much more on feel, just instinct of how poems should be ordered.

BKR: Your book’s title, Normal They Napalm the Cottonfields, comes from the poem “Cottonballs.” Can you discuss what it means and why you chose it as the title?

DLP: Yes, "Cottonballs" is the title poem. It's dedicated to my friend and common partner in exploration and hiking, Keith, who informed me of the fact that some farmers use actual napalm to make harvest easier. In October and November, you can drive by the cottonfields and smell the napalm choking the local air. The poem shows the irony of the beauty of the cotton and the farms but also the brutality of convenience and the false superiority of technology and so-called progress.

BKR: As Grace Cavalieri points out, your poems are “large with social conscience and awareness.” In your poem “Fort Story Shoreline Fenced Off For Homeland Insecurity” the reader is left with the image of the ocean as it “drags that barbed wire/ out to sea.” The speaker shares a secret laugh with the Cape Henry lighthouses as nature triumphs over politics. Do you think poetry can be a vehicle for social change? What else do you think socially conscious poems can “do”?

DLP: "Fort Story Shoreline Fenced Off for Homeland Insecurity" is a 100% true story. After decades of access, seemingly all of a sudden, we citizens and taxpayers were stopped from walking the tip of the North End of Virginia Beach in 2018. Why? No explanation. It's not security; it's paranoia "evolving" into oppression. As an artist, I feel obligated to speak out and up, especially for the voiceless, from nature to justice. I have no doubt poetry and other art forms push social change. Two favorite examples are Philip Levine's "They Feed They Lion" and Gwendolyn Brooks' "A Bronzeville Mother Loiters In Mississippi. Meanwhile a Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon."

BKR: There is a connection between your poetry and the photo series you’ve been posting over the years to social media called “Beauty of Decay.” So much so that your photograph “Green House” graces the cover of your book. Can you say a little bit about how the series began, how it’s evolved, and what you hope people will take away from it?

DLP: Poetry was my first artistic love (with music), and my area of study as well, but photography is an amateur passion indeed. My brother, Greg, a vastly superior visual artist, inspired me years ago to get a real camera (I use a Canon SX1IS) and work on photography. My series, Beauty of Decay, evolved from rides and hikes through the country to the realization that I could preserve collapsing farmhouses and barns, abandoned tractors, trucks and churches, etc., as nature repossessed them. I hope people will see the beauty and process of nature but also the significance of farms and farm history.

Left to right, one-four, from DL Pearlman's series "Beauty of Decay". Linda Blaskey and Andrew Greeley award DL Pearlman his big check at the Dogfish Head Inn in Lewes, DE.

BKR: Whether one views your collection as “regionalism” or “poetry of place,” one can’t deny its landscape resonates with both the feeling of home as well as an overwhelming sense of impermanence. In the poem “Old City Walls” you write, “Invisible Wisdom gusts like wind:/ never take the word of a mockingbird/ or the only permanence is decay.” And in “Lens,” you echo, “i photo decay as a way/ of dealing with my own.” How does Norfolk and the surrounding region inspire this sense of mortality and wasting away or is it your own sense of mortality that recognizes a kinship in the landscape of the region?

DLP: We as humans (or perhaps Americans) love to deny or ignore that we live next to death every minute of every day. That's not morbid; it's real, and there is no reason, beyond fear, to pretend otherwise. Reading this, for instance, will result in the death of a few minutes. It's ok. In A Bird in the Hand Is a Dumb Bird, a poem called "Authentic Xerxes II Toenail Clipper" asks "Can a beachcomber cover his windowsills / with conchs and sand dollars / and deny he has circled himself with death?" My hometown of Norfolk dates to 1682, and through war, disease (a yellow fever outbreak in 1855 killed one-third of the population, for instance), and other ills of humanity, wisdom and perspective still get passed down. To acknowledge mortality should amplify carpe diem, not pessimism or bitterness.

BKR: What obsessions, experiences, or poetic influences would you say have contributed to your own personal poetics?

DLP: I am rather obsessed with truth. I much prefer brutal, even difficult, truth to gold-coated bullshit. I feel the need to be artistically honest, no need for games, fronts, façades, censorship, or outright selfish lies, and I hope readers feel and know this. Furthermore, there is no need to hide emotion, as this is another common and accepted form of dishonesty. To that end, experience is the best inspiration. Write what you know is excellent and proper philosophy. I often try to get my English 111 students to stop writing about dragons and princesses and start focusing on funny or sad moments of their lives. Beginning students of writing need to know that their life experiences are plenty important and valid as potential subjects for artistic expression.

BKR: Can you talk a little bit about your day job teaching at Tidewater Community College? How important is it to you to participate in events like judging the Norfolk State University poetry slam?

DLP: Although I could use a serious raise, I very much enjoy teaching at Tidewater Community College. My colleagues in English are kind human beings and fine teachers, and the students demonstrate their potential with passionate classroom discussions, if not their homework. Even though I may have to battle a bit against writing in text/emoji-speak, students do not lack ideas or vision. They educate me every school day. As for judging, it's been my privilege to judge for Norfolk State, the Anna David Rosenberg Poetry Award, Hampton Roads Youth Poets, and others. I currently judge the high school level in the Poetry Society of Virginia's annual contest.

BKR: What’s next for you? Do you have a new project you’re working on?

DLP: As for what's next, art is ongoing, and my senses are wide open. I hope to do more readings and poetry workshops, and continue to explore and preserve the underknown.

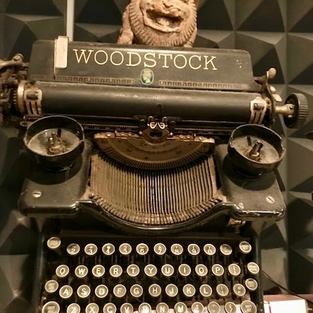

BKR: Your bio says, “Pearlman serves seven typewriters and nine guitars…” How do you serve them and what are their demands?

DLP: I like typewriters. I own seven, two of which rest on my mantelpiece. I don't use any of them much, but one, an early 1960s Smith-Corona my father bought new, is my go-to for envelopes. It hums confidently and features no lowercase, only smaller and larger uppercase. I also herd guitars. When I jam with anyone willing, I most often ride my green Ibanez Talman, not the most expensive electric guitar but with plenty of heart and guts. Both typewriters and guitars are magical machines, just like the pen. They all demand love and attention, and I try to deliver. I need to dust.

* * *

Thanks to D.L. Pearlman for agreeing to be interviewed and for his engaging responses. This interview was conducted by Kari Ann Ebert. Ebert was recently awarded an Individual Artist Fellowship by the Delaware Division of the Arts (2019). Winner of the 2018 Gigantic Sequins Poetry Contest and the 2019 Crossroads Ekphrastic Writing Contest, her work has appeared in Mojave River Review, Philadelphia Stories, The Broadkill Review, and Gargoyle as well as several anthologies. She lives in Dover, Delaware where she enjoys making up-cycled art and collaborating with local artists, musicians, and writers.

Opmerkingen